About the Series

This three-part series is inspired and informed by Limits to Growth and its subsequent editions. In it, we will explore systems dynamics questions, and use Machinations models to answer them.

In our first Limits to Growth article, we explored why the world’s population has grown. This time, we begin to explore what causes populations to decline – including, perhaps, our own.

We begin with the following question:

Why is the population still growing if birth rates are declining?

The instinct when thinking about systems is to imagine them as a simple set of inflows and outflows, like a bathtub with a tap and a drain:

In this case, births are the inflow, deaths are the outflow, and the population is the water. By this analogy, if the number of births is less than or equal to the number of deaths, the population cannot increase.

While the bathtub analogy works well for simple systems, it doesn’t work as well for ones with feedback loops, ones where the contents of the metaphorical bathtub has an effect on how much flows in or out.

In the case of population, the inflow of the system (births) is not just a faucet releasing a fixed amount over time. It is also affected by how many people there are: more people equals more births.

What the bathtub analogy also misses out when applied to population growth is that there are actually two “birth” variables: the absolute births occurring, and the number of births per person (known also as the birth rate per capita, or the fertility rate).

What we actually mean when we say “birth rates are going down” is not that the absolute number of births is decreasing; rather, that the number of births per person is decreasing.

Though we’ve clarified our original question – Why is the population still growing if birth rates per capita are decreasing? – we still haven’t answered it. To do so, we need a more sophisticated model than our bathtub analogy.

The Model

This Machinations model builds on the bathtub analogy to explain why the population can still increase even though the birth rate per capita is going down.

Each step (or increment) in the model represents the passage of an entire lifetime: everyone born in the last step dies in the next. This keeps things simple and consistent with the basic principle of the bathtub analogy.

The Absolute Births component is the first departure from the bathtub analogy: for each person in the population (more specifically, each woman, i.e. half the total), the inflow of new births is increased by the Birth Rate. In our bathtub analogy, it is as if the amount of water in the tub causes the tap to be turned up more, such that the flow of water increases.

In this model, we also assume the Birth Rate declines by 7% each step (i.e. every lifetime). In the bathtub analogy, this is like the tap being turned up ever more slowly: crucially, it is not that the tap is being turned off altogether.

Hit Play and notice that the initial population of ten million people does grow, and continues to grow for a while before finally declining.

The Machinations model makes the answer to our question seem quite obvious: just because the birth rate per capita is declining, it doesn’t necessarily mean that absolute births are also declining.

In essence what is happening is an arms race between two competing forces: the declining birth rate per person, and the number of people around to give birth. If the negative feedback effect of the declining birth rate is stronger than the positive feedback effect of population growth, the population will grow: if the reverse is true, the population will decline.

Finding the tipping point

There exists a point in our model at which the population shifts from growth to decline, where the birth rate is too low for the population to fully replenish itself.

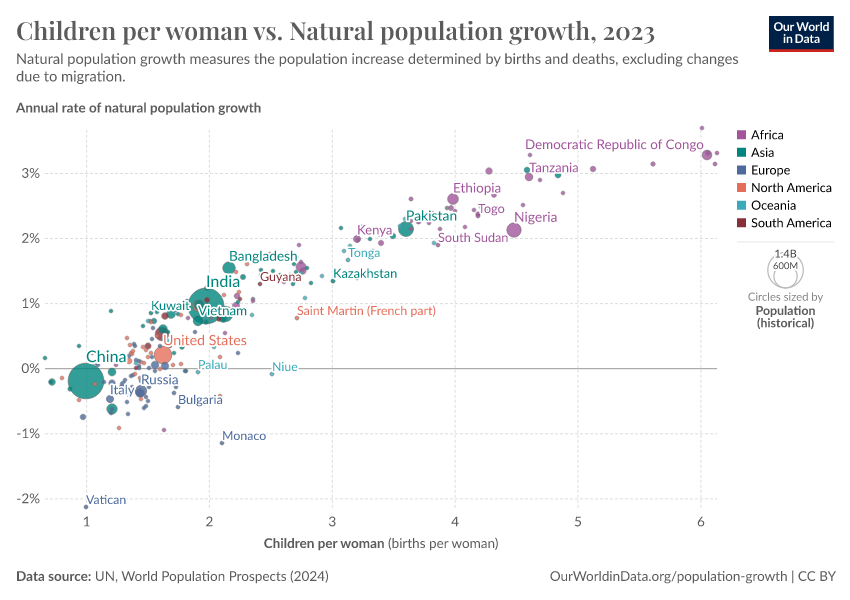

In the real world, the precise birth rate that describes this tipping point is called the replacement fertility rate. A population below the replacement fertility rate will eventually start to shrink.

The replacement fertility rate can be calculated mathematically, though it can also be observed in our model: when the birth rate falls below 2 (i.e. two children born for every woman), the population begins to decline.

To prove this to yourself, make a copy of the model and set the % Birth Decline to 0, so that the birth rate remains constant. Then, modify the Initial Births per Woman. Notice that any value greater than 2 will lead to perpetual population growth, whereas any value less than 2 will lead to perpetual population decline. Only at exactly 2 does the population stay the same.

The reason for this value of 2 is because two parents are needed to produce a child: if each couple had only one child, the population would halve at every generation. Thus, assuming no premature deaths, a couple would need exactly two children to take their place when they die.

Predictably, the reason that the replacement fertility rate of all nations is somewhat greater than 2 is because some people die before reproducing, something which our model doesn’t account for. The higher the mortality rate, the greater the replacement fertility rate.

This relationship between mortality and replacement fertility rates also explains why pre-industrial societies had more children: when the risk of death is higher, a population must produce more children, lest it slowly go extinct.

Conclusion

It would appear that we have answered (and clarified) our original question of why populations can still grow even if their per capita birth rate is declining:

First, we clarified that a decline in birth rate is not the same as a decline in total births; and that what is declining is the rate at which the population is growing, not the actual size of the population.

This clarification led us to a precise answer to the question: so long as the birth rate remains above the replacement fertility rate of at least 2, the population will continue to grow.

With this answer in mind, it would seem reasonable to assume that the reverse is also true: that if the birth rate falls below the replacement fertility rate, the population must fall.

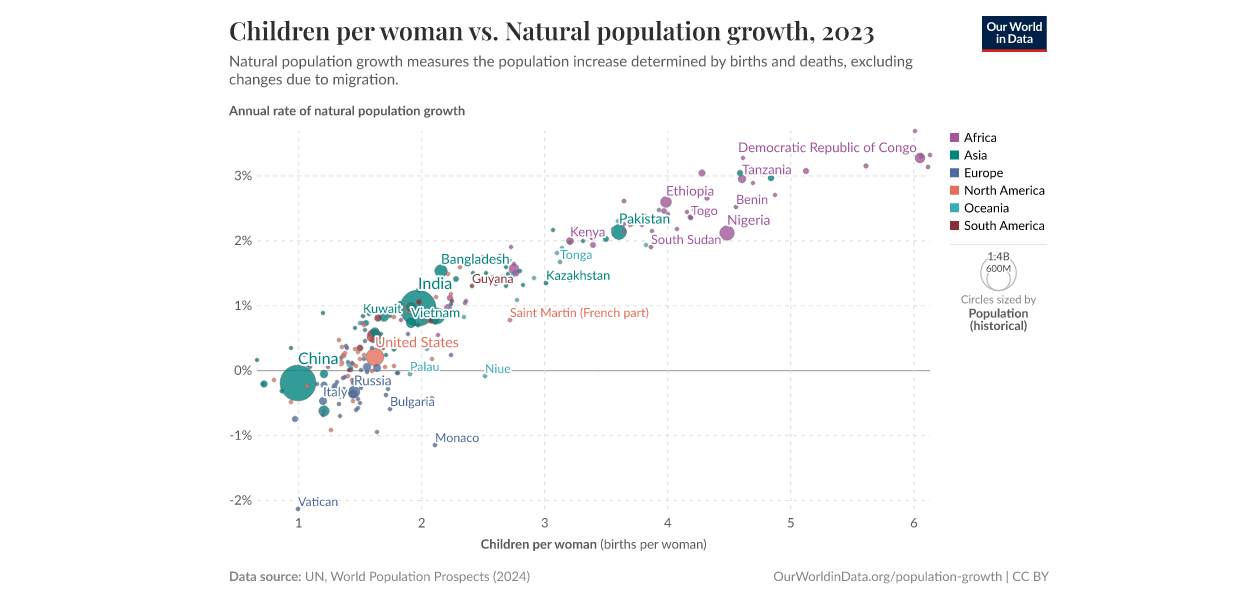

This is not the case. In fact, many of the developed countries in the world are now below replacement fertility rate – yet their populations continue to grow. How can this be the case, given that the same logic works in reverse?

To understand why, we will need to adapt and improve our existing model. This will be the subject of the next article: Understanding the delayed effects of birth rate changes