About the Series

This three-part series is inspired and informed by Limits to Growth and its subsequent editions. In it, we will explore systems dynamics questions, and use Machinations models to answer them.

This time, the question relates to the human population:

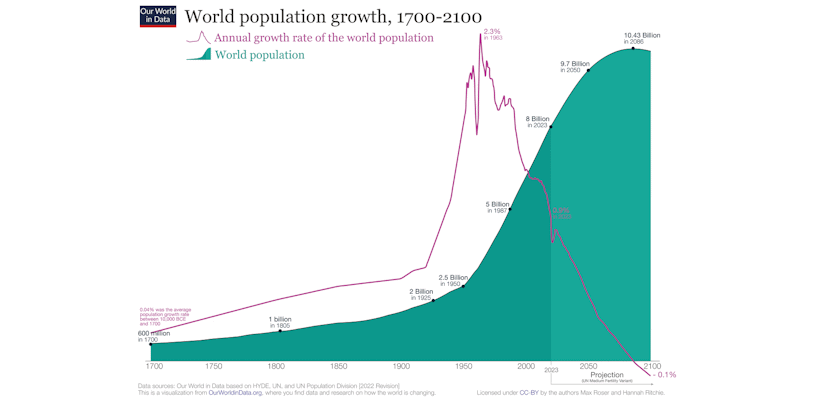

What exactly has caused the surge in population over the last several centuries?

The answer typically given is that innovations in medicine, manufacturing, agriculture and other sectors have all caused a dramatic fall in mortality rates.

This answer is correct, of course, but the specifics are lost.

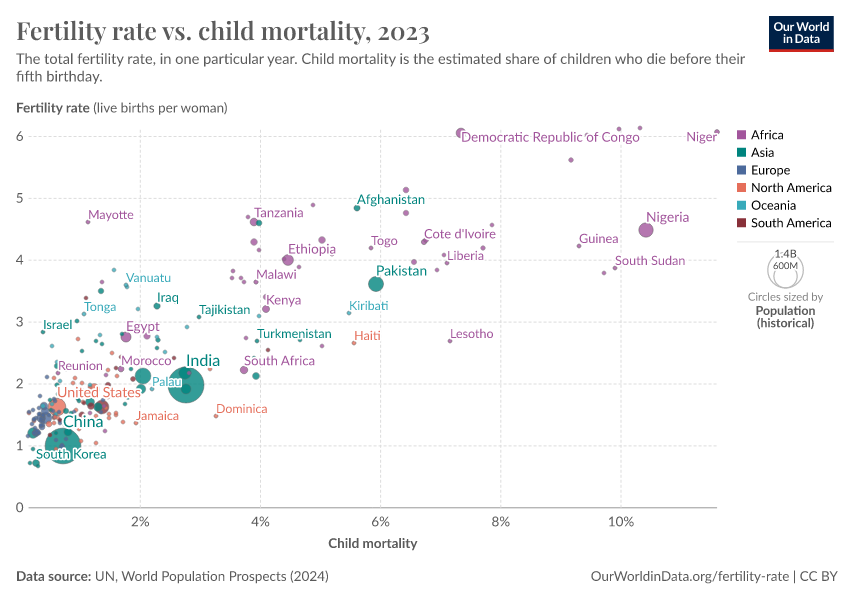

Though it is true that major technological advancements have allowed the population to grow, it is also true that populations with higher mortality rates tend to have more children, and vice versa.

This positive relationship between mortality and birth rate is fuelled in part by the harsh reality that a population must produce enough children to replace the ones that die: the greater the risk of death, the more extra children that are needed.

Without a more nuanced answer to our question about population growth, this fact about mortality seems contradictory: if technological change reduced mortality rates and allowed couples to have fewer children, why did the population grow so quickly regardless?

A systems dynamics model can provide this more nuanced answer.

Modelling Population

The model below represents a pre-industrial world, where infant and adult mortality is high, as was the number of children born per woman.

Each step (or increment) in the model represents the passage of a generation, with any surviving members of one age group transitioning into the next.

Hit Play and notice that the population, as was the case before the Industrial Revolution, remains roughly the same: the societal and institutional incentives are such that women have just the amount of children needed to sustain the population on average. More affluent families may have fewer children, but the vast majority of people, who remain in poverty, bring that average up.

Now click on the Source called NEW INNOVATION.

With this new innovation – which could represent any number of things, such as the invention of the vaccine – comes a reduction in the mortality rates of children and adults. This causes a surge in the population: women are still having the same number of children, yet more of those children are surviving to adulthood. This in turn leads to more adults having children of their own.

Notice that the number of children per woman did fall as well. However, this reduction in children born was delayed: it takes at least a generation for families, and the culture more broadly, to adjust to the sudden reduction in mortality rates (represented in the model by the Pool called Improvements in Family Planning).

In addition to technological innovations, there are also political and societal advancements, most notably those that gave women more autonomy and reproductive freedom. Without these advancements, the restrictions placed upon women would act as a buffer against a compensatory fall in family sizes.

Conclusion

Rapid changes in the mortality rates of a population, and the delayed feedback loop that leads women to opt for fewer children, combine to produce a growing population.

This dynamic is echoed in the modern age, where the many children and grandchildren of the post-WWII baby boom are still multiplying. Only now, more than half a century later, is that rapid growth beginning to dissipate.

In fact, in many developed countries, the birth rate is now low enough that populations will eventually begin to shrink.

We will explore why in our next article: Understanding what causes population decline