Limits to Growth Explained #3: Understanding the delayed effects of birth rate changes

About the Series

This three-part series is inspired and informed by Limits to Growth and its subsequent editions. In it, we will explore systems dynamics questions, and use Machinations models to answer them.

Our conclusions so far

In our last Limits to Growth article, we used our model to understand why developed, post-industrial populations can decline:

The model suggests that if the fertility rate (births per woman) is less than around 2, the population will diminish. This critical value of 2 (assuming no non-natural deaths) is the replacement fertility rate.

However, we also noted that many of the developed countries already have a fertility rate less than 2, and yet they are still growing year-on-year.

While the model we built is technically correct in what it sets out to show, it is too imprecise to resolve this apparent paradox.

This is because the time-scale of the model is too long: one step in the model represents an entire lifetime (about 75 years). Thus, any nuance about generational dynamics is lost.

It is true that seventy-five years of below-replacement fertility will cause the population to decline, but that’s not useful for us if we want to know what will happen in the next few years or decades.

Refining the model

To allow us to understand better the dynamics of population decline, we’ve improved upon the model:

Instead of a whole lifetime passing in a single step, this new version has a time-scale of ten years. This means we can see what happens to each ten-year age demographic individually.

Each ten-year age demographic is represented in a separate pool, with all people in that group moving to the next age group at each step. Once again, we’ve disregarded non-natural deaths for simplicity.

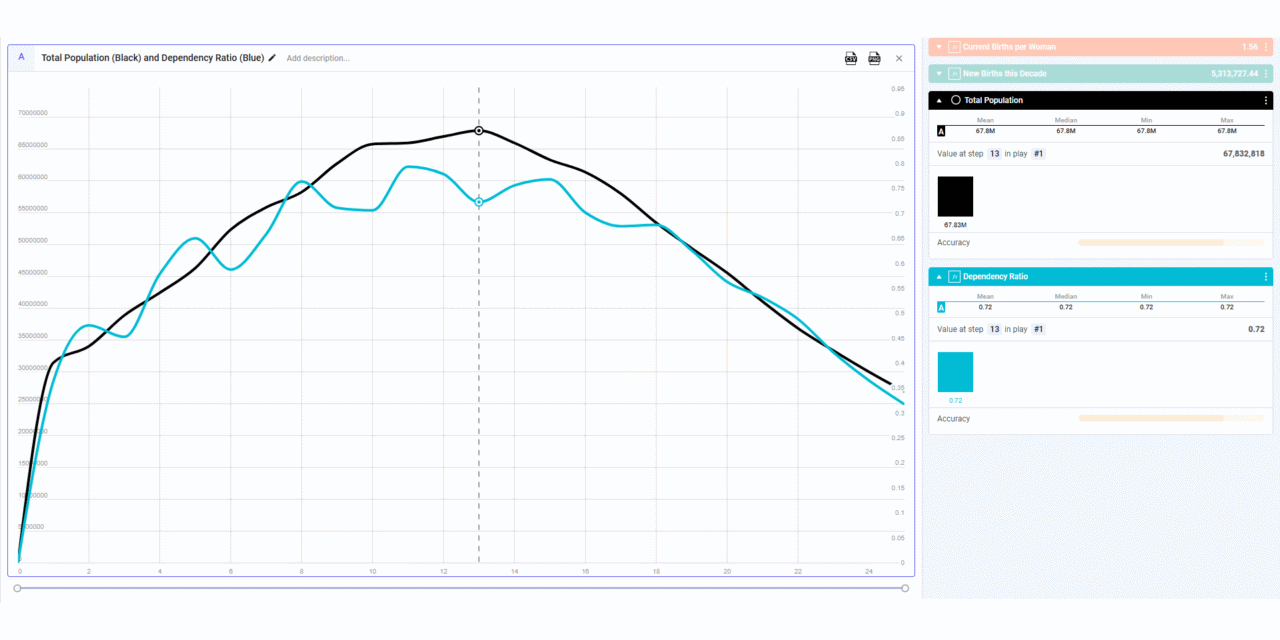

Hit Play and observe what happens to the Total Population in our refined model as the Current Births per Woman declines decade-by-decade.

This time, even when the average Births per Woman falls below the replacement fertility rate of 2, the population continues to grow for a while. With a more precise time interval in the model, we can now understand why.

Explaining the results

Only Women of Reproductive Age (twenty to forty in our model) can produce new children. These new children in turn only reach reproductive age in about two decades subsequently. This means that the birth rate today sets the foundation for the absolute number of births in 2-4 decades’ time.

This in turn means that if there is a sudden but temporary surge in birth rates, up or down, the population may only feel that shift several decades down the line. The same is true if infant mortality declines suddenly (see our first article). In the bathtub analogy we described last time, changes in birth rate can be thought of as a long delay between turning on the tap and the rate of water flow actually changing.

Further to the delayed dynamics of birth rates, deaths are also delayed: after aging out of their fertility window, adults have roughly four decades left to live, in which they are still counted towards the total population. In the bathtub analogy, this can be thought of like a slowly draining sink: any sudden surge in the inflow of people takes an entire lifetime to flow out via natural death.

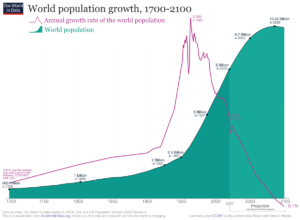

These two delayed effects are the reason it takes several decades for the population to “catch up” with what is happening to the birth rate. This simultaneously explains why populations below replacement rate can go on growing for a while, and also why it took several decades for the post-WWII baby boom to truly kick in.

In essence, what we missed in our simplified model was what happens in the time between the initial population explosion and the natural deaths of those born during it.

The dangers of declining birth rates

Our new model has shown that, though it may take several decades, populations below replacement rate will eventually decline.

Some argue that this is ok: that a slightly smaller population is ideal for the sustainability of our planet. This may be true, however such broad claims can easily lead to dangerous misunderstandings.

In our model, we’ve counted several subcategories of the population: Infants, the Elderly, Working Adults and, crucially, Dependents.

Dependents are individuals who cannot work, and must be supported by the labour of Working Adults. Dependents include Infants and the Elderly.

The model also calculates the Dependency Ratio of the population, a real-world measure used to indicate the relative burden on the working population: the greater the proportion of the population that cannot work (i.e. Dependents), the lower the Dependency Ratio; the lower the Dependency Ratio, the greater the quantity of labour the working population must supply to support its Dependents.

Run the model again and notice what happens to the Dependency Ratio over time.

Initially, as the population increases, so does the Dependency Ratio: the burden of labour per working adult decreases. However, the reverse occurs when the population starts to decline.

As the population declines and birth rates with it, the more abundant generations of the past half-century begin to age and become dependent. With fewer children being born, the burden on those children will be greater when they reach adulthood.

Without significant improvements in the efficiency of labour or an increase in automation – or increased fitness and lifespan among the elderly – future generations will face greater hardship in the form of the labour demanded of them.

This fact reveals the danger of simply stating that “a smaller population is more ideal”: reducing the population in every age group equally might be ideal, but what’s actually likely to happen is that the decision of today’s adults to have fewer children will lead to a disproportionately large elderly population.

This, as we have seen, is a dangerous situation to be in.

Conclusion

Using our Machinations models, we’ve demonstrated the nuances of population growth and decline and their causes. We’ve also identified some of the dangers of rapid changes in birth rates.

Though the models we’ve built thus far do not use data from real populations, the dynamics at play hold mostly true in the developed world: birth rates have often fallen below replacement rates, and continue to decline further. Eventually, we will reach the tail end of the population boom of the last century, and populations will begin to decline.

Given the rapid changes – both up and down – in absolute births over the last two centuries, any further shifts in birth rates are liable to cause even more unpredictability and instability. In fact, even if the birth rates of all developed countries were to stop declining as of today, the outcome would still be problematic, precisely because many of them are already below their replacement birth rates.

Unfortunately, no model can predict the future perfectly, and it takes a very well-informed one to produce at least somewhat accurate predictions. Hopefully, however, understanding the fundamental dynamics of population growth and decline will give individuals a better sense of what the future might be like.